On Aug. 30, 2024, a visionary teacher and pilot who played an integral role in Wings of Hope’s history peacefully passed away at the age of 101. We were fortunate to speak with Mike Stimac a few weeks before his passing and are grateful for his contribution to the early days of Wings of Hope.

Mike Stimac was a science and math teacher, pilot and adventurer who dedicated his life to teaching young people and helping others. In the early 1960s, Stimac was teaching at St. Joseph’s, an all-boys Catholic high school run by the Marianists in Cleveland. Beloved by his students, Stimac started a ham radio club that tracked Sputnik, the first satellite in space. He also established an aviation ground school which later evolved into a program to help students get their pilot licenses. In 1962, the Marianists told Stimac there was a need for a science and math teacher at a Catholic school they operated in Nairobi, Kenya. Stimac accepted the assignment at Mangu High School and quickly established an amateur radio club — one of his students would be the first Kenyan to get an amateur radio license — an electronics club and an aviation program. All these programs are still going strong today!

Stimac’s first connection to Wings of Hope was Bishop Joseph Houlihan, who had set up a network of missionary medical clinics to serve people throughout the African desert. The bishop needed an efficient way to travel from clinic to clinic. He had a plane, a Super Cub that had been donated and ferried to Kenya by Bud Donovan and Jerry Fay. (Read the last issue of LIFT for their story.) But the bishop was waiting on a Catholic nun, Sister Michael Therese Ryan of the Medical Missionaries of Mary, to earn her pilot’s license in Boston before she could join him in Africa as the first flying nun transporting people and supplies to the medical outposts.

While awaiting the sister’s arrival, the bishop learned that a teacher at Mangu High School was a pilot. He drove out to the high school and asked Stimac if he would fly him to the clinics.

According to Stimac, Houlihan was a man you couldn’t refuse. He remembered the bishop as “a dominant figure in the mission territory” who was known for having the connections with church and government authorities that were needed to get things done.

Stimac was happy to support the bishop’s work — flying the bishop, people and supplies between the medical clinics — but he also saw it as an educational opportunity for his students.

“Because I was connected with education, my tendency was always to bring it back to the kids,” said Stimac.

The Mangu High School aviation program flourished under the tutelage of Stimac who would personally operate the bulldozer that carved out a runway for the school in a nearby field.

In the summer of 1963, Sister Ryan finally arrived in Kenya with her pilot’s license fresh in hand. But the sister had no experience in bush flying which requires a unique set of skills to safely take off and land on short, make-shift runways. Stimac spent the next several weeks teaching Sister Ryan how to fly in the bush and taking her on orientation flights to each of the medical outposts.

In 1964, the Marianists called Stimac back to Ohio to resume his teaching career there. He also used his time in the states to raise money and handle airplane donations for the nonprofit he established to support the African missionary work: United Missionary Air Training and Transport — or UMATT.

According to Stimac, “what was needed was promotion — a live specimen out of Africa to speak directly to the crowd,” and Stimac was happy to oblige.

He shared exciting stories of UMATT’s missionary work helping the people of Kenya using an airplane and a flying nun, and sympathetic Americans responded with generous donations of cash and airplanes.

“As the work in Kenya and East Africa matured, we ended up having a couple of dedicated airplanes. Also, young people who wanted to build up time on their flight record would come out and fly for the operation at no cost, only their subsistence being taken care of,” Stimac recalled. “They got an invaluable experience, and it was at a minimal cost — and we were able to keep the operation going. That was how the thing grew up, and that’s also how a core of bush pilots emerged out of this operation.”

As Stimac managed UMATT from Ohio, Sister Ryan continued flying missions in the Super Cub, which was quickly deteriorating due to harsh desert conditions and some hungry hyenas that apparently liked the taste of its fabric wings.

Halfway around the world in St. Louis, Joe Fabick and Bill Edwards, friends and businessmen who had learned of the plight of the flying nun and the Super Cub from Bishop Houlihan, were raising money to send a new metal Cessna to Kenya to support UMATT’s work.

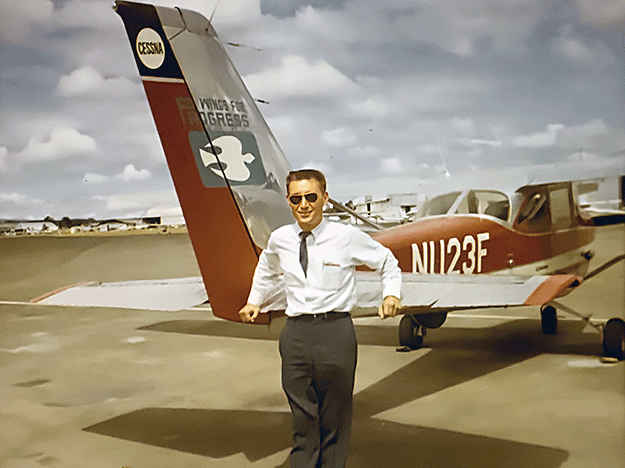

In the spring of 1965, the Marianists sent Stimac back to Africa. And in May of that year, he found himself in Rome meeting up with Max Conrad, a professional pilot who had been commissioned to fly the new Cessna from St. Louis to Nairobi. After an audience with Pope Paul VI, who blessed the UMATT banner and the work of the missionaries in Africa, Stimac flew with Conrad to Nairobi where Bishop Houlihan, Sister Ryan and the Medical Missionaries of Mary would use it to continue the good work of providing people throughout the desert region access to medical care and supplies.

UMATT would continue to grow in Africa, eventually becoming Wings for Progress and then Wings Over Africa. Stimac would continue helping the organization as a volunteer pilot and fundraiser and, eventually, would finish out his career conducting pilot ground training for Trans World Airlines in Saudi Arabia.

Back in St. Louis, Fabick and Edwards marveled at the impact UMATT was making with the one Cessna they had supplied and wondered how much more they could accomplish with more planes sent to more locations around the globe.

This inspired Fabick, Edwards and a few others to found Wings of Hope. More than six decades later, their vision for using planes to change and save lives — which was inspired, in part, by the work of a science teacher from Ohio — continues to impact thousands of people

around the world every year.